Baba Yaga's Suitcase © 2014

I am fascinated by the Russian forest witch, Baba Yaga, who eats you if you are lazy and wasteful or unlucky, and rewards you if you are industrious or lucky. She is reflected in the German Gingerbread House witch, and the Pacific Northwest basket ogre. In my imagination, she has been conquered. We have chainsaws and bulldozers, and all she has is a chicken-footed hut. Nevertheless, she still lurks in the forest, thinking her cannibalistic thoughts and gathering her power.

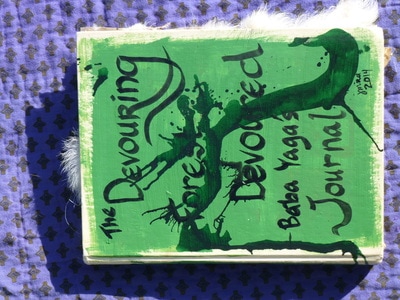

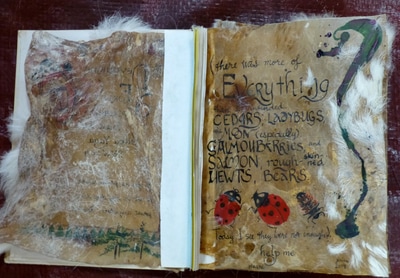

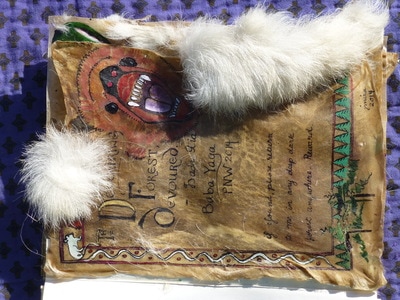

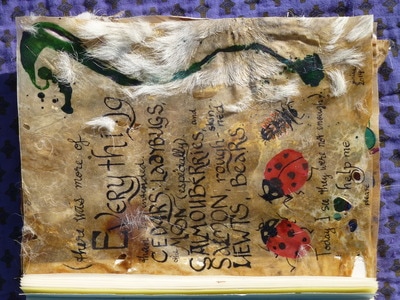

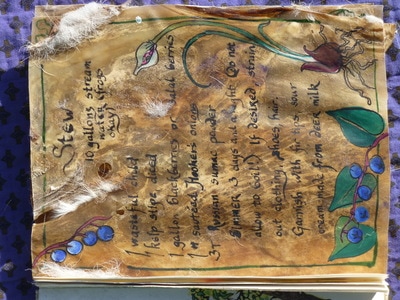

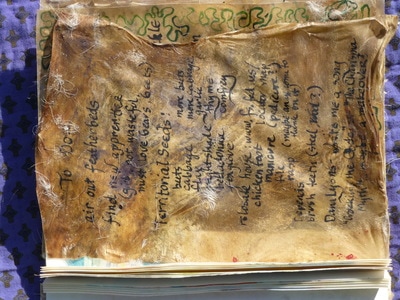

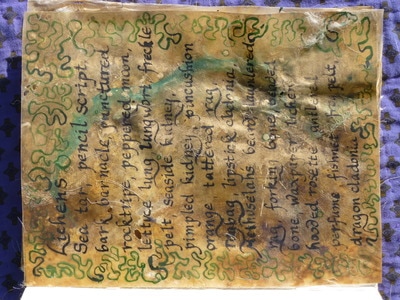

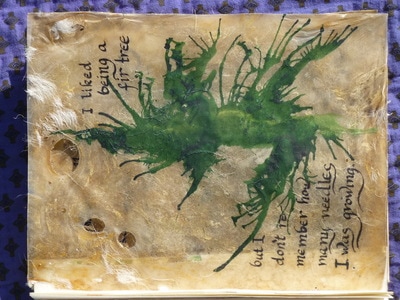

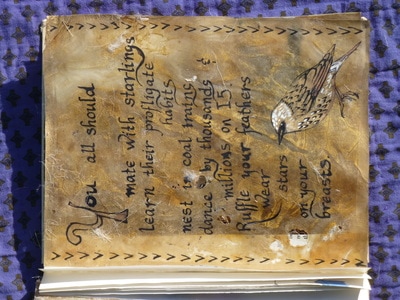

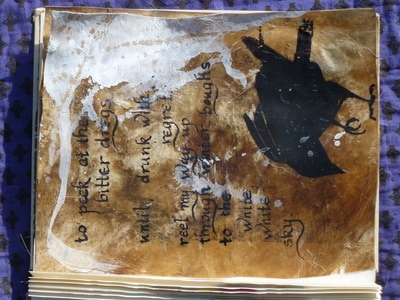

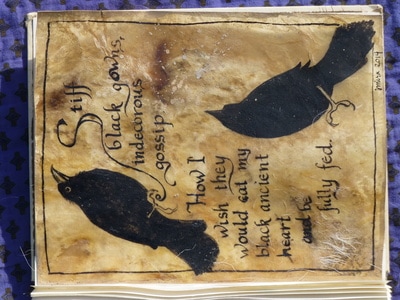

For a recycled art show at Allied Arts, I found a moldy suitcase in a barn and glued in a portrait of one of my ex's lovers, dotted with origami moths folded from paper in the recycle bin. I collected moth-eaten balls of yarn, and the tail ends of wool that didn't fit in the skeins I spun to sell at crafts fairs, and knit them into a rather spectacular cape. I found a pile of sheep offal on the beach that a farmer had left for the eagles, vultures, and other scavengers, and collected the hides that hadn't already rotted through. From them, I made a journal of calligraphed poems. I also stretched a particularly stinky hide across the top of one of those ubiquitous white buckets that had split in its long life as a sheep water bucket, and painted ravens on it. I also made a scary fortune telling deck, with tachinid flies, tent caterpillars, and crows. People actually asked me to tell their fortune with it! What could they possibly have been thinking, with cards like that? We are so accustomed to cleaned-up fairy tales nowadays, that we have forgotten about the ones that end in cannibalism, dismemberment, and despair. I'm not saying it's time to bring that back, but that it is already here and we have decided not to notice. Go ahead. Ask me to tell your fortune.

For a recycled art show at Allied Arts, I found a moldy suitcase in a barn and glued in a portrait of one of my ex's lovers, dotted with origami moths folded from paper in the recycle bin. I collected moth-eaten balls of yarn, and the tail ends of wool that didn't fit in the skeins I spun to sell at crafts fairs, and knit them into a rather spectacular cape. I found a pile of sheep offal on the beach that a farmer had left for the eagles, vultures, and other scavengers, and collected the hides that hadn't already rotted through. From them, I made a journal of calligraphed poems. I also stretched a particularly stinky hide across the top of one of those ubiquitous white buckets that had split in its long life as a sheep water bucket, and painted ravens on it. I also made a scary fortune telling deck, with tachinid flies, tent caterpillars, and crows. People actually asked me to tell their fortune with it! What could they possibly have been thinking, with cards like that? We are so accustomed to cleaned-up fairy tales nowadays, that we have forgotten about the ones that end in cannibalism, dismemberment, and despair. I'm not saying it's time to bring that back, but that it is already here and we have decided not to notice. Go ahead. Ask me to tell your fortune.

Storyteller's Desk, © 2010

What would a culture look like if it were just as contemporary as ours, just as "advanced," but was embedded in nature instead of at war with it?

I came up with a world in which people live in tribes that are tied to their ecosystems, just as the remaining indigenous peoples of the world still are. Since I live in the San Juans, I wondered what it would mean if the Island Marble Butterfly were not teetering on the edge of extinction. What if I called our tribe the Butterfly Folk? What would they be like?

For one thing, they use the Island Marble as metaphor. Caterpillars come out in spring and eat until they form chrysalids, which overwinter. The mature butterfly comes out the next spring. The Butterfly Folk use this as a metaphor for the greed of immaturity. After a winter's worth of meditation and isolation, initiates emerge as adults with attention to spiritual matters as well as material things.

"The Greedy Monster" (see below) Is a tale of initiation and rebirth. Many of the Butterfly Folk's artifacts reflect the importance of this story (which, of course, is not reproduced here exactly as it appears in the secret rites).

The storytellers not only keep traditions and stories alive, but play an active role in the initiation ceremonies. Above is a desk used by one of the storytellers. You can see she finds the prairie habitat of the Island Marble Butterfly particularly inspiring.

I came up with a world in which people live in tribes that are tied to their ecosystems, just as the remaining indigenous peoples of the world still are. Since I live in the San Juans, I wondered what it would mean if the Island Marble Butterfly were not teetering on the edge of extinction. What if I called our tribe the Butterfly Folk? What would they be like?

For one thing, they use the Island Marble as metaphor. Caterpillars come out in spring and eat until they form chrysalids, which overwinter. The mature butterfly comes out the next spring. The Butterfly Folk use this as a metaphor for the greed of immaturity. After a winter's worth of meditation and isolation, initiates emerge as adults with attention to spiritual matters as well as material things.

"The Greedy Monster" (see below) Is a tale of initiation and rebirth. Many of the Butterfly Folk's artifacts reflect the importance of this story (which, of course, is not reproduced here exactly as it appears in the secret rites).

The storytellers not only keep traditions and stories alive, but play an active role in the initiation ceremonies. Above is a desk used by one of the storytellers. You can see she finds the prairie habitat of the Island Marble Butterfly particularly inspiring.

Contents of Storyteller's Desk

This is an ongoing project. Right now, the Storyteller's Desk has the following items in it:

1. "The Greedy Monster" book, with handmade paper made from prairie plants (see below for text).

2. "At the Sign of the Mustard and Butterfly" book, a short story taking place at a biology lab in one of the villages (see below for text).

3. A quill pen (I'm trying to figure out how to get my homemade kiln hot enough. I've been making little ink pots from local clay, but so far they only fire to terra-cotta and "breathe" water. I'm experimenting with glazes, bellows, and possibly simply rebuilding the kiln to get a hotter firing temperature. If I'm ever successful, the kit will include a set of clay pots with soot-based and walnut-based ink. Maybe there's a way to mordant the ephemeral inks I've made from other substances. This is the work of years, I think, so don't expect those filled ink pots too soon!)

4. A box of beaded bones, to be used when telling the story of "The Greedy Monster."

5. A soft heart with hard beads embroidered in the shape of a butterfly.

6. A cedar tassel, included for mysterious reasons.

7. A journal explaining how the items were made; the only anachronism in this desk.

1. "The Greedy Monster" book, with handmade paper made from prairie plants (see below for text).

2. "At the Sign of the Mustard and Butterfly" book, a short story taking place at a biology lab in one of the villages (see below for text).

3. A quill pen (I'm trying to figure out how to get my homemade kiln hot enough. I've been making little ink pots from local clay, but so far they only fire to terra-cotta and "breathe" water. I'm experimenting with glazes, bellows, and possibly simply rebuilding the kiln to get a hotter firing temperature. If I'm ever successful, the kit will include a set of clay pots with soot-based and walnut-based ink. Maybe there's a way to mordant the ephemeral inks I've made from other substances. This is the work of years, I think, so don't expect those filled ink pots too soon!)

4. A box of beaded bones, to be used when telling the story of "The Greedy Monster."

5. A soft heart with hard beads embroidered in the shape of a butterfly.

6. A cedar tassel, included for mysterious reasons.

7. A journal explaining how the items were made; the only anachronism in this desk.

Storyteller's Kit

Telling "The Greedy Monster" must be very elaborate (I don't know for sure, because I haven't been initiated). There are two drums, an eight-sided one painted with a closeup of a caterpillar head, and a seven-sided one painted with a closeup of a butterfly head. There is a large woolen shawl in a scale pattern, big enough to wrap oneself up like a chrysalis (with a few bits poking out).

The Greedy Monster

One spring there was a giant, who stomped around the countryside (so they say).

Every one of her hundred feet was so big and so clumsy (like a galvanized trash can).

Every one of her eyes was like one of those DVD’s (rainbow flat, they say that).

Her mouth was hard but it could have been bigger (she thought).

So she used her hands to stuff food into that greedy mouth (so they say).

She was strong and curvy, like one of those belly dancers (the fat ones).

So, one day, they say, a clammy flat grey day, a wrung out dish rag day (that kind of day),

She stomped around the countryside with her trash can feet (it was loud),

Eating everything in her path; tents and kayaks, strings of fish (they were good),

Geese and bluebird nests, camas gardens, even outhouses (they weren’t so good).

She met an old man with a decorated hat, and he said stop (he meant it),

But she couldn’t stop, she ate him up without thinking (he crunched),

And then she met a student in a pretty dress, who ran away (but not fast enough),

And then she ate a blond boy who was playing in a treehouse (his friends escaped).

In front of her was harmony, behind her was like an untuned banjo (chaos).

That day there was nothing left in the village, everything was gone (eaten flat).

That night she didn’t even regret how much she’d eaten (but her tummy hurt),

And she closed her ears against the crying, nothing to do with her (so what).

She arched her back, thrashing her head back and forth, snarling (like a catfight),

Her tummy hurt, her skin hurt more, and then it came right off (like a glove),

Underneath there was a new skin, and by daylight she was hungry (and bigger),

Forgetting the pain of the night, she stomped out and started again (so they say)

Eating everything in her path, but she couldn’t stay where she was (it was eaten),

She stomped over to the next village and ate through that one too (so they say),

She ate three people too, people who were trying to stop her (they died).

So, that night, she burst out of her new skin and grew another one (sleek),

And ignored all the crying and carrying on from the two villages (they were history).

On the third day she ate another village and another three people (too bad),

On the third night she left her skin behind and grew another one (lots of wriggling),

By then there was nothing left to eat, not for three villages around (she’d eaten everything).

Now she cried, cried rivers, and the wind came up, wind and rain (a gale),

The bones of the people she had eaten got up and started walking around (in her gut),

They tickled at first, but then it hurt. She rolled around and cried (rivers),

But that didn’t help. She didn’t have friends. People were afraid of her (with reason).

But the bones were not afraid, “How can she hurt us now?” they said (in dry voices),

So they started to dance inside her gut, while outside it rained tears (big ones).

The more they danced, the more fun they had in there, inside that monster (while she cried).

The dancing bones were dry in there, and outside was nothing but misery (her fault).

The monster was thrashing around, and when her feet hit the ground (clumsy feet),

They went “Crash!” and when she howled the sky shook and turned violet (it scared her).

The dancing bones danced harder and the monster was rolling around (like boiling water),

She was like an excavator all by herself, digging holes with her big feet (mud flew everywhere),

Biting things and spitting them out, and howling in the rain (she was noisy).

Then the villagers came and stood nearby with ropes, stakes, and ladders (they were mad),

When a length of her body flopped near some people (so they say),

They threw a rope over it and staked it down on both sides (dangerous work).

Finally, the monster was pinned down in the mud and the rain stopped (the wind too).

The people could hear those bones dancing like crazy inside her (their neighbors).

“Are you there?” they called to the bones, but the bones weren’t listening (they were dancing).

The monster was groaning like a tree in the wind. At last she shut her eyes (finally),

And the villagers finished the job of tying her down with ropes and stakes (so they say).

They found blue poly tarps and spread them over her curled up body (lots of tarps),

Then they went away to take care of all the things they had to do (rebuilding their houses).

But the dancing bones wouldn’t stop dancing, in fact, they danced harder (every day),

Kicking their feet and throwing their arms around, whirling and jumping (like leaves in fall).

Their hard feet sliced her guts up, their waving arms churned her insides (to jelly).

“What are you doing in there?” she asked them. “Dancing,” they said (in the dark).

“When will you stop?” she asked them. “Not ‘til weary time sits down” (forever).

All winter, the bones danced around in her soupy guts, clattering away (full of energy),

In spring, the monster stopped groaning and said, “I want to dance too.” (they thought she’d died).

The dancing bones sat down, surprised, and waited to see how she would do that (escape from the tarps).

All that dancing had moved the parts of her body around, and she just slid out (rotten ropes).

She stood out there in the sun looking around. Everything was new (green and fresh).

The bones started dancing and then she spread her wings and flew (to meet the clouds).

Every one of her hundred feet was so big and so clumsy (like a galvanized trash can).

Every one of her eyes was like one of those DVD’s (rainbow flat, they say that).

Her mouth was hard but it could have been bigger (she thought).

So she used her hands to stuff food into that greedy mouth (so they say).

She was strong and curvy, like one of those belly dancers (the fat ones).

So, one day, they say, a clammy flat grey day, a wrung out dish rag day (that kind of day),

She stomped around the countryside with her trash can feet (it was loud),

Eating everything in her path; tents and kayaks, strings of fish (they were good),

Geese and bluebird nests, camas gardens, even outhouses (they weren’t so good).

She met an old man with a decorated hat, and he said stop (he meant it),

But she couldn’t stop, she ate him up without thinking (he crunched),

And then she met a student in a pretty dress, who ran away (but not fast enough),

And then she ate a blond boy who was playing in a treehouse (his friends escaped).

In front of her was harmony, behind her was like an untuned banjo (chaos).

That day there was nothing left in the village, everything was gone (eaten flat).

That night she didn’t even regret how much she’d eaten (but her tummy hurt),

And she closed her ears against the crying, nothing to do with her (so what).

She arched her back, thrashing her head back and forth, snarling (like a catfight),

Her tummy hurt, her skin hurt more, and then it came right off (like a glove),

Underneath there was a new skin, and by daylight she was hungry (and bigger),

Forgetting the pain of the night, she stomped out and started again (so they say)

Eating everything in her path, but she couldn’t stay where she was (it was eaten),

She stomped over to the next village and ate through that one too (so they say),

She ate three people too, people who were trying to stop her (they died).

So, that night, she burst out of her new skin and grew another one (sleek),

And ignored all the crying and carrying on from the two villages (they were history).

On the third day she ate another village and another three people (too bad),

On the third night she left her skin behind and grew another one (lots of wriggling),

By then there was nothing left to eat, not for three villages around (she’d eaten everything).

Now she cried, cried rivers, and the wind came up, wind and rain (a gale),

The bones of the people she had eaten got up and started walking around (in her gut),

They tickled at first, but then it hurt. She rolled around and cried (rivers),

But that didn’t help. She didn’t have friends. People were afraid of her (with reason).

But the bones were not afraid, “How can she hurt us now?” they said (in dry voices),

So they started to dance inside her gut, while outside it rained tears (big ones).

The more they danced, the more fun they had in there, inside that monster (while she cried).

The dancing bones were dry in there, and outside was nothing but misery (her fault).

The monster was thrashing around, and when her feet hit the ground (clumsy feet),

They went “Crash!” and when she howled the sky shook and turned violet (it scared her).

The dancing bones danced harder and the monster was rolling around (like boiling water),

She was like an excavator all by herself, digging holes with her big feet (mud flew everywhere),

Biting things and spitting them out, and howling in the rain (she was noisy).

Then the villagers came and stood nearby with ropes, stakes, and ladders (they were mad),

When a length of her body flopped near some people (so they say),

They threw a rope over it and staked it down on both sides (dangerous work).

Finally, the monster was pinned down in the mud and the rain stopped (the wind too).

The people could hear those bones dancing like crazy inside her (their neighbors).

“Are you there?” they called to the bones, but the bones weren’t listening (they were dancing).

The monster was groaning like a tree in the wind. At last she shut her eyes (finally),

And the villagers finished the job of tying her down with ropes and stakes (so they say).

They found blue poly tarps and spread them over her curled up body (lots of tarps),

Then they went away to take care of all the things they had to do (rebuilding their houses).

But the dancing bones wouldn’t stop dancing, in fact, they danced harder (every day),

Kicking their feet and throwing their arms around, whirling and jumping (like leaves in fall).

Their hard feet sliced her guts up, their waving arms churned her insides (to jelly).

“What are you doing in there?” she asked them. “Dancing,” they said (in the dark).

“When will you stop?” she asked them. “Not ‘til weary time sits down” (forever).

All winter, the bones danced around in her soupy guts, clattering away (full of energy),

In spring, the monster stopped groaning and said, “I want to dance too.” (they thought she’d died).

The dancing bones sat down, surprised, and waited to see how she would do that (escape from the tarps).

All that dancing had moved the parts of her body around, and she just slid out (rotten ropes).

She stood out there in the sun looking around. Everything was new (green and fresh).

The bones started dancing and then she spread her wings and flew (to meet the clouds).

At the Sign of the Mustard and Butterfly

Carved dogwood spoons make a distinct noise against clay bowls, heavy and comfortable. We were drinking nettle soup, delicate with spring mussels at the bottom and mustard flowers floating on top. One of mine had a yellow spider, which a maid carried out to the yard. I was watching the spider, because Bard Jennie was telling a story that had me in it, and I would just as soon have her never know who that inept character had been. I’ve got my secrets. Jennie’s a new one to our Folk, and she and I do not get along. She thinks I’m after her job, which I’m not. Well, in a way, I guess I am. Or was. A crop of interns dressed from all over the Northwest were crowded at the table that was usually mine, and of course they’d never heard Jennie’s particular brand of malice and wisdom before. They listened and laughed and clapped along with the chorus, and I drank soup.

It was this time of year last year, that she was singing about. My sister Daika and I had gone off to the sheep meadow. We were collecting mustard blossoms for Mother, who was, as usual, going to serve her signature nettle-mussel soup at the Mustard and Butterfly for the spring influx of travelers. The meadow sat just like it is today, fringed with fir trees like a monk’s tonsure except for the sand cliffs at the west overlooking the channel, with fox and rabbit holes mounding and caving the soil so that we could never run through the flowers like we wanted to, with our eyes closed and our mouths open and the world ours for the spending.

We had big baskets on our backs, and Daika brought her shawl and a picnic in case we wanted to stay out there all day. She was a year older than me, seventeen, getting ready for her initiation winter and not all that happy about it. Me, I wanted to stay a caterpillar forever. Still do, ribs of the world I do.

“Hey, greedy caterpillar,” she said, “You’ll finish my basket for me?”

“Yah,” I said, “but you owe me.”

“Oh, I’ll help a bit, kiddo,” she said, sighing dramatically and picking a mustard flower. “Hey! This one has a caterpillar on it!”

“I know,” I said. “Most of them do. There are a lot of wild ones this year.”

“I don’t see the point. Why have wild caterpillars if you can have the kind in the sheds, that make silk?” She ran her fingers through her gown, something shimmering in black.

She was already a chrysalid, seems like, dressing in black like that and dreaming in the middle of the teeming clatter of our days. When she wasn’t mooning around wishing for things she couldn’t name, she was angry at hypocrisy, especially Mother’s and Dad’s, but generally, everybody’s. I miss her.

Me, I was sucking life in and getting fat on it, with my hungry open mouth and my evil thoughts about girls, any girls, young, old, or printed on paper, and the way I followed John Pignose around making him show me everything in his meadowlark lab and then some. I wanted to be John Pignose when I reached adult phase, or at least be his intern, that’s what I thought then, but also, I never wanted to be adult. Earth’s teeth, I was right. He was working on meadowlarks and ballads, as everyone knows by now. Can they be taught regular human stories to sing? Sure enough, they loved to learn them, but sure enough, they changed them something terrible. John had me remember the stories perfectly so I could scold the larks when they twisted them. I swear, some of those birds were like, well, birdbrains. Like they’d studied at the feet of crows. Tricksters, all of them. But I loved the ballads myself.

So Daika took her collecting basket and spent maybe half an hour picking Mother’s dinner fixings, and then she left me to it. “You’ll dump out whatever I collected anyway, for being too wilted, or too this or that, I don’t know James, and then fill both of them to the top. I’m going out to look at the whales. Yeah, I’ll remember. I owe you.”

Fair enough. I liked the mechanical pleasure of picking flowers, and, to be honest, liked that my dearly beloved sister was somewhere else. I picked for some time, but then finally her words penetrated my thick skull. Whales?

Sure enough, I hadn’t noticed the whales, didn’t much care to, but there they were out in the grey glitter of the ocean, back up from calving in Mexico. They were greys, and really, all you see is hundreds of foggy spots on the water, and grey blodges with the sharper images of the Eschrictius Clan people riding on their backs, all decked out in their yellow and orange wetsuits. Same old, every year. When I was freshly hatched, of course, Mother used to take us out to watch and they’d sometimes come close and wave, but I’ve outgrown that. Daika, no. Every year, there she goes clambering down the cliff trail to swim out to them, something that no sensible islander from around here does. We’ve all seen orcas converge on a calf and try to rip its tongue out, and we’ve seen how the greys will protect them, and the people swimming around with their secret Eschrictius Clan weapons (that aren’t so secret, John Pignose said, but he wouldn’t say more), driving off the orcas, and the blood, and then they all swim on, and you never know quite what happened, whether the calf would live, or the orcas starve, or what happened. Does Daika care? No, she swam out every year, every time another pod goes by. Now I know why, but at the time, it seemed plain crazy.

The whale clans are all a bit paranoid, from the days when they were first formed and whale oil was such a precious commodity people would actually kill whales to get at their oil. Good thing we have biolights now, that want to help us see, and all the rest of the biotech things. But the whales remember, and they say you can’t be too careful.

Anyway, there she swam, I don’t know how she stood the cold, and then here came the orcas, and there was a lot of distant shouting and churning and blood and slapping the water and Daika kept swimming thataways instead of back to shore. Why in the name of earth’s long leg bones I could not tell you, then.

Then there were more shouts, lots of them, and the orcas skyhopping and the greys swimming north and the blood in the water spreading, spreading, and I saw it had been a calf and a big one, maybe the mother. “Daika!” I yelled, but she kept swimming. Earth’s teeth, should I go in after her? She was older than me, and a strong swimmer, while I only wimped around in the shallows maybe twice a summer. Yelling seemed to be the only thing to do, so I did it until my voice was hoarse. Also, I was running towards the cliff trail, and of course, that was the day that I stuck my foot into a hole and snapped my fibula just at the ankle, and, Earth’s ever loving leg bones, that hurt.

Which means I missed all the rest of what happened. I was rolling around feeling sorry for myself and making noises I hadn’t made since I was three. I didn’t see Daika and one of the youths from Eschrictius Clan come ashore. He must have looked an ugly fellow in that garish wetsuit, all swirled and speckled with yellow and orange designs. His face looked like a moon, I saw later, outlined in the tight-fitting red cap he wore, and speckled with moles. Daika always loved the moon, and she had apparently fallen in love with this guy several seasons back, just based on that moon face, I guess, and her romantic idea of what an Eschrictius man must be like.

The two of them sat on the beach for the longest time, kissing and carrying on. Talking, for all I know. It was Sally Darningneedle who found me. She was one of Mother’s interns, come to us from Seattle, looking to learn our wildcraft cooking. Cooks come in two sizes, it seems, one hard and round, and the other hard and thin. She was the hard and thin kind, not too happy to take time out to find out what was keeping Daika and me. “James,” she yelled as she trotted out into the meadow, the green and yellow silks of her gown matching the colors of the mustard plants and making her look like an animated plant. I wasn’t paying much attention to her words by then.

She picked up the full basket as though it were my fault that my bone was sticking out of my skin and said, “You stay here, I’ll get help. Where’s your sister?”

I didn’t answer, so the two of them had another hour or so on the beach together before I was taken care of and Sally went out again, looking for Daika. Her resemblance to an angry mustard plant was remarked on by Mother, so it wasn’t just me.

Luckily we had a healer staying the season with us, an incredibly tall woman, freckled with straying red hair tending to grey and, like many middle-aged women, with a Kali-kit, an extra set of arms temporarily bio-attached. She’d brought a whole muleload of equipment, with x-ray machine, angiogenesis enzymes, growth hormones, the works. It took almost a week before I could walk again, though. I don’t know why they can’t speed it up.

I spent the time propped up in John Pignose’s lab, learning more ballads and singing to the birds. John’s got a secret technique he wouldn’t tell me about, but I think it’s something to do with splicing altered neuropsin onto the genes that help them remember songs. Our meadowlarks are modified already, of course, and have been for a hundred years. We thought they needed a bit of help against the habitat changes they’d experienced since our human population expanded the way it did, and gave them a bit more memory and a bit more lifespan. What did they do with it? Not what you’d expect, no population expansion, no territory expansion. Well, actually, a bit of both, but that’s not what was important. What they did do, was go song happy. You couldn’t go anywhere without a meadowlark singing its head off at you.

John’s spent half his life working with the larks on that. The larks want to help, of course, we put that in a hundred years ago. They stood in line for the chance to get in on his ballad project, and he’s brought in dozens of bards over the years to feed them songs. Some of them can only learn one per breeding season, others can stuff five or six into their tiny little heads. Nobody knows if they understand them, but the males sure enjoy singing them, and their womenfolk? They remind me of human opera buffs.

So, I was singing when Alexsander and Daika came in, entwined with each other as though they’d invented lust and had to make sure not to forget any of the moves lest a single second of inattention made them forget. They made a dramatic couple, him so dark and her so fair. I’d spent so many years with Daika as my big sister, it made me stupidly jealous to see another guy put his hands on her. Wasn’t anything I wanted to do about it, though, nothing that I wouldn’t regret later.

Anyway, there they were. “Hey, James,” said Daika. “I’m just showing Alexsander around.”

“Good,” I said in a voice that meant “Bad.”

She ignored my snippiness. “We just came from the silkworm sheds. He’s never seen such big caterpillars before, have you Alexsander?”

“Nope,” said Alexsander, his thick pink lips forming the word in a shape that exactly matched the shape of his face. His voice was as deep a voice as I’ve ever heard. Maybe voice modification was something the northern clans liked to do, or maybe he was born with it.

“They only like the gene-mod salal we grow,” I said helpfully, just to show I didn’t hate his guts for touching my sister. Which I did, of course. Also, he had an edgy look to him that I didn’t like.

“I already told him about our operation,” said Daika. “How much silk comes from their cocoons, how they’re free to fly where ever but have to come back here to lay their eggs.”

Alexsander grinned, but it didn’t look like it came from the heart. It was a grin pasted on over some deep emotion. “Interesting, nothing like the cryotech stuff we do up in the Arctic.”

John Pignose wanted to hear all about that, but I certainly didn’t. Alexsander, with Daika hanging on him disgustingly, drifted off with John while I went back to the lark I was trying to teach. It’s not as easy as you would think. Last year, this fellow wanted that children’s song in 3/4 time about the greedy monster, but this year I couldn’t get him interested in anything in 3/4. I finally found one in 6/8, one of the jig-time harvest dances, and he was hopping around with excitement. I sang him the first verse about ten times before he had it letter perfect, though. John gets impatient with me if I take more than two repeats to get a song right, but that’s birds for you. Not an ounce more memory than they need in their heads, if that. Maybe I was a bit short with him because my setting fibula bone was itching like crazy.

I’d just finished with that lark and a new one was clamoring to begin, when Alexsander showed up, jittering his thumbs against his legs. “Where’s Daika?” I asked him.

“She’s gone back to help at the inn,” he said. “Said to stay here and watch you work.”

“Did she?” I was dubious.

He nodded. “I told her I sing, and she said I’d be interested in what you’re doing.”

I guess anyone would be. Pride of work took over, and I let the next lark in. He’d been fluttering impatiently at the window for some time. He was even less easy to please than the last one. No, nothing in 3/4. Nothing in 6/8. No 4/4 either. Well, that was just about all I knew to sing, back then.

“Mind if I try?” asked Alexsander. “I only do the one kind of song, though.”

“Suit yourself.”

He cleared his throat a few times. Sweat beaded on his nose and upper lip. He cleared his throat, gave a kind of whimper, and began. It was something Arctic and dark, his deep voice setting up resonances in my chest. A very odd sensation. One, two, three, boom, pause. One, two, three, boom, pause. “In spring nineteen two Mary Fisher,” and then he stomped his foot and paused, “Had a baby who wasn’t her husband’s,” stomp, pause, “Who loved him but sometimes he’d hit him,” stomp, pause, “And one day he broke the kid’s ribcage,” stomp, pause.

It went on and on for ten or more verses, a disjointed story that didn’t seem to have much of a point except to list misery and betrayal. I was not impressed.

The lark was. He pranced around excitedly, always a clear signal. Encouraged, Alexsander sang it to him again, and it took very few repeats before the bird had it down, several octaves higher, and flew off to impress the ladies with it.

John Pignose had wandered up to listen. “That’s quite a song you have there, Alexsander,” he said.

Alexsander looked miserable and nodded. “Yah. I’m burning my bridges,” he said with a very strange laugh.

“What do you mean?”

“Is that the time? I’ve got to run and help Daika,” he said, and rushed out the door, knocking over one of the perches as he did.

Over the next few days, Alexsander took over my job, to the point where I asked John Pignose if it was okay to teach the larks such brutal stuff. Adultery, abuse, and murderous pique, was that what we wanted our sweet birds to be learning? Alexsander wasn’t getting much pleasure out of the exercise, looked like.

“Well, James,” said John in his slow way, “we’ve got hundreds of birds out there singing thousands of ballads from around here. Now, they’ve got another kind of tune to spread to the world. I can’t help but think that diversity is good, whether in species or in song.”

“Yeah, but I don’t like them.”

“That lad has something on his mind,” said John. “But as for the songs? You’d do well to learn them yourself. You never know when that kind of rhythm and lyrics will come in handy.”

So I learned them, couldn’t help it really, not with my enhanced genetics and John’s training. There were over a hundred, one for each year since 1902, each one gloomier than the last.

“What’s the significance of 1902?” I finally asked Alexsander, the day before my leg healed and I could walk again.

“Well,” he said, and blushed. His skin was dark to start with, but even so, you could tell he was blushing because it got darker, and because a fine sweat suddenly sprang out on his forehead. “Well, it’s when we started.”

“No way,” I said, rudely. “I know my politics at least well enough to know that your Eschrictius clan was founded pretty much when whites came to the Northwest, back in the 1700’s sometime.”

“Well, yeah,” he said. “True. But it’s when my job was made.”

“And that would be?”

But he wouldn’t tell me, and got very uncomfortable. That night, he and Daika went on an even longer walk than usual. Talking, I thought to myself, and sniggered.

When neither of them showed up for work at the inn the next morning, Mother recruited me instead. “What do you think of Alexsander?” she asked me as we ground kelp into powder. As long as it was only for a few hours at a time, I loved helping Mother. The Mustard and Butterfly had an enormous earth oven, with stovetop, warmer, and twin bread ovens dividing the kitchen from the dining hall. It was always warm in there, and there was always something a growing boy could nibble on, and I loved the smell and the physicality of food. Plus, that was the last day of my healing and I’d gotten tired of John Pignose’s lab and having to watch the larks pick Alexsander’s tunes over mine.

“Don’t like him,” I said.

Mother actually laughed. “He’s a sweet boy,” she said. “But I think something’s weighing on his mind.”

“Daika’s weighing on his arm,” I said, sulkily.

“True enough. It happens,” said Mother. “Don’t stop work just because we’re talking, James.”

“Sorry.”

“You don’t know what it is?” she asked.

“Mom, he’s Daika’s age, not mine. He’s not going to tell me his secrets. And if he did, would I tell you?”

Mother laughed again. “I had to try,” she said. “He is dating my daughter. I don’t want her in over her head. At least I got him to take off that uncomfortable wetsuit and put on something more sensible.”

“Dating? What’s that supposed to mean?”

And then we had a long discussion of antiquated courtship terms, reminding me once again of how much things have changed since the dinosaur days of my parents.

As is often the way of such things, that afternoon Alexsander did tell me his secrets. I’d been sleeping on a bench in John Pignose’s lab and when I woke up, there was Alexsander, holding a mug of cold mint tea for me. “You got a minute?” he asked, and I nodded blearily, slurping at the tea.

“What happens to those birds?”

“What do you mean, what happens to those birds?”

“Well, what are you going to do to them?”

“We’re not going to do anything to them. What, you eat larks in the Arctic?”

Alexsander looked unhappy. “Fish and krill, mostly.”

“Krill?”

“Shrimp.”

“Oh.” There was a silence. I slurped a bit.

“So, what happens to the birds?”

“You keep asking that,” I said, impatiently. “Why don’t you just tell me what you are after.”

Alexsander looked even more unhappy. Then he got up and started pacing, his fists clenched. His moon face rode above his stocky body, like on a smoky night when there’s a fire set somewhere in the forest and the sky is raining ash. “You remember I told John I was burning my bridges?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, maybe I didn’t really mean it. Maybe I just was upset about what happened to Ooolooa and her calf. I tried to stop her, but that was a terrible thing to do, she’d rather die than let her baby die.” His face suddenly crumpled horribly and I was afraid he was going to cry, but he got ahold of himself. “And getting thrown off her back into the herring-filled waters off your island.”

“You don’t seem too upset about my sister, though.” I was a nasty teenager, I admit it.

Alexsander sat on the bench, keeping well clear of my almost healed ankle. “Your sister is fine, James. Don’t worry.” He put his head in his hands. “It’s me that isn’t fine, and Ooolooa that’s dead.”

I bit my tongue. Even I could tell that the value of smart-ass remarks was a bit skimpy.

“So, will you please tell me what you are going to do with those larks?”

“I told you. Nothing. They just fly away with a new song to sing.”

Alexsander did not take his head out of his hands. “Away? Where do they fly?”

“How should I know? I don’t ask them for an itinerary. They can’t write, anyway.” I began to giggle. “Why, you don’t like the idea of them singing your songs? You shouldn’t have butted in and sung them, that’s what.”

Alexsander got up and started pacing again. He was not a happy guy. “I shouldn’t have sung them.”

“Why not?”

“I’m the Secret Keeper.”

“So, they are secret?”

He groaned. “Not any more.”

Now I was more curious than irritated. “So, what kind of Secret Keeper tells the birds everything?”

“A very bad one,” said Alexsander. His voice cracked. “There’s nothing worse. I betrayed my people, for nothing more than grieving for my friend’s baby, for nothing more than being in a new land and thinking that nobody here could ever care about what goes on in my clan.”

“We learn about that early,” I said.

“Learn about what?”

“It’s for when we go on our Fluttering.”

Alexsander sighed. “And what would that be?”

“It’s after your initiation, you go off to flutter around for a year or two, or five, looking around, learning stuff that might be useful to the Butterfly Folk, maybe even finding a new place to live for a few decades or a lifetime. Most of us come back, but still.”

“Yes, so what is it you learn early, then?” asked Alexsander.

I shook my head. “I guess you guys must not have a Fluttering.”

“Whales don’t flutter.”

“Right. Anyway, they tell us that it’s easy to think that nothing you do in another tribe’s territory matters. That they’re not deep-down people, that all their strange customs means they don’t have customs at all. Nope, they tell us. Don’t go doing stuff that would make another one of the Butterfly Folk raise their eyebrows. Everyone that comes back says it’s a temptation.”

“I know,” said Alexsander. “It is.”

“So, they should have sent you through Orientation here. We tell our foreign interns the same and make sure they know it before we let them loose.”

“I’m not an intern. I don’t even know what one is.”

“I can tell. Same as a Fluttering, they all call it something different. Student, intern, apprentice.”

“I know apprentice.”

“Right. They come here to learn, and either stay or go on or go home. But we don’t let them crash around our lands without some kind of moral compass.”

Alexsander sat down again and put his head in his hands again. “So, I just betrayed my people, and you say that’s normal?”

“No, it isn’t normal. We usually listen to our teachers. Don’t you have teachers up there?”

Alexsander nodded. “The whales.”

“That’s it?” I tried to imagine what it would be like to be taught by a butterfly, and failed. Well, maybe we have learned from them. But still. Just whales?

“That’s it,” said Alexsander. His shoulders were tensed right up to his ears. “I can never go home.”

That was when John Pignose walked in. “What do you mean, you can never go home?”

Alexsander shook his head.

Well, I didn’t owe him anything. “He says he shouldn’t have taught those songs to the larks. They were a secret.”

John’s lined face looked grave. He’s an odd-looking man, and nobody can tell whether he got that way through gene-mod or was born ugly. I think that big nose helps him a lot when he’s working; he seems to work by smell as much as by sight or touch. Certainly, he doesn’t have any trouble with chemical analysis while the rest of us have to mess with dozens of reagents and enzymes and such. Anyway, his face looked grave. “How much of a secret?” he asked.

I thought back to the lyrics. Adultery, murder, and spite. “Pretty much,” I said. “If those songs were true, he’s just embarrassed dozens of people, maybe hundreds, big time.”

“Hundreds,” said Alexsander.

“So, they were true? Earth’s heart and liver!” John looked very upset. “Do you think your people will try to come down and kill our larks?”

I sat up. This was terrible. “War, you mean?”

Alexsander shook his head over and over. “I don’t know. I can’t go home, can I?”

“I doubt it,” I said, but he was looking at John.

“I doubt it,” said John. “Will anyone come to find you? What is a Secret Keeper? I’ve heard about them but what exactly do you do?”

“No,” said Alexsander. “Ooolooa and her calf died, I was riding her, and then I was gone. It happens. They’ll think I’m dead. And I might as well be.”

“So, what is a Secret Keeper?”

“Truth,” said Alexsander. “No tribe works well without somebody knowing the truth, they get unbalanced and can’t make good decisions.”

“True enough,” said John.

“But nobody wants their neighbors to know the bad stuff. So they tell the Secret Keeper.”

“And what does the Secret Keeper do with that knowledge?”

“Nothing,” said Alexsander. “We’re just supposed to know about it.”

We thought about that.

“So,” said John Pignose, “You’re new to the job?”

“Apprentice,” said Alexsander, miserably.

The next morning, my leg was finally healed, the adults had been talking all night with Alexsander, and he was sent off in tears with a mule and enough supplies to get him to the center of the continent before he had to stop and talk to anybody. The following morning, Daika was gone, and Mother was angry and snappish all day. She did send another mule after her, though, but Daika has yet to send word, and yet to pay me back for collecting those mustard flower heads for her.

Me, I spent the rest of season wandering around listening to larks in the field. Nobody ever swam ashore to see if our birds were singing their secrets out for everyone to hear, and really, nobody I couldn’t get the idea of Secret Keeper out of my mind, though. I started up my own list of secrets. I learned to swim. I watched the whales as they went by, imagining what it would be like to wear a red cap. To know everybody’s secrets and to keep the truth in sight.

The spring after my initiation year, some interns came and some went. Jennie the Bard joined us and I hope you don’t remember me just from her ballads. On a cloudy day in April, I pulled Alexsander’s wetsuit on and swam out to the whales as they went north.

It was this time of year last year, that she was singing about. My sister Daika and I had gone off to the sheep meadow. We were collecting mustard blossoms for Mother, who was, as usual, going to serve her signature nettle-mussel soup at the Mustard and Butterfly for the spring influx of travelers. The meadow sat just like it is today, fringed with fir trees like a monk’s tonsure except for the sand cliffs at the west overlooking the channel, with fox and rabbit holes mounding and caving the soil so that we could never run through the flowers like we wanted to, with our eyes closed and our mouths open and the world ours for the spending.

We had big baskets on our backs, and Daika brought her shawl and a picnic in case we wanted to stay out there all day. She was a year older than me, seventeen, getting ready for her initiation winter and not all that happy about it. Me, I wanted to stay a caterpillar forever. Still do, ribs of the world I do.

“Hey, greedy caterpillar,” she said, “You’ll finish my basket for me?”

“Yah,” I said, “but you owe me.”

“Oh, I’ll help a bit, kiddo,” she said, sighing dramatically and picking a mustard flower. “Hey! This one has a caterpillar on it!”

“I know,” I said. “Most of them do. There are a lot of wild ones this year.”

“I don’t see the point. Why have wild caterpillars if you can have the kind in the sheds, that make silk?” She ran her fingers through her gown, something shimmering in black.

She was already a chrysalid, seems like, dressing in black like that and dreaming in the middle of the teeming clatter of our days. When she wasn’t mooning around wishing for things she couldn’t name, she was angry at hypocrisy, especially Mother’s and Dad’s, but generally, everybody’s. I miss her.

Me, I was sucking life in and getting fat on it, with my hungry open mouth and my evil thoughts about girls, any girls, young, old, or printed on paper, and the way I followed John Pignose around making him show me everything in his meadowlark lab and then some. I wanted to be John Pignose when I reached adult phase, or at least be his intern, that’s what I thought then, but also, I never wanted to be adult. Earth’s teeth, I was right. He was working on meadowlarks and ballads, as everyone knows by now. Can they be taught regular human stories to sing? Sure enough, they loved to learn them, but sure enough, they changed them something terrible. John had me remember the stories perfectly so I could scold the larks when they twisted them. I swear, some of those birds were like, well, birdbrains. Like they’d studied at the feet of crows. Tricksters, all of them. But I loved the ballads myself.

So Daika took her collecting basket and spent maybe half an hour picking Mother’s dinner fixings, and then she left me to it. “You’ll dump out whatever I collected anyway, for being too wilted, or too this or that, I don’t know James, and then fill both of them to the top. I’m going out to look at the whales. Yeah, I’ll remember. I owe you.”

Fair enough. I liked the mechanical pleasure of picking flowers, and, to be honest, liked that my dearly beloved sister was somewhere else. I picked for some time, but then finally her words penetrated my thick skull. Whales?

Sure enough, I hadn’t noticed the whales, didn’t much care to, but there they were out in the grey glitter of the ocean, back up from calving in Mexico. They were greys, and really, all you see is hundreds of foggy spots on the water, and grey blodges with the sharper images of the Eschrictius Clan people riding on their backs, all decked out in their yellow and orange wetsuits. Same old, every year. When I was freshly hatched, of course, Mother used to take us out to watch and they’d sometimes come close and wave, but I’ve outgrown that. Daika, no. Every year, there she goes clambering down the cliff trail to swim out to them, something that no sensible islander from around here does. We’ve all seen orcas converge on a calf and try to rip its tongue out, and we’ve seen how the greys will protect them, and the people swimming around with their secret Eschrictius Clan weapons (that aren’t so secret, John Pignose said, but he wouldn’t say more), driving off the orcas, and the blood, and then they all swim on, and you never know quite what happened, whether the calf would live, or the orcas starve, or what happened. Does Daika care? No, she swam out every year, every time another pod goes by. Now I know why, but at the time, it seemed plain crazy.

The whale clans are all a bit paranoid, from the days when they were first formed and whale oil was such a precious commodity people would actually kill whales to get at their oil. Good thing we have biolights now, that want to help us see, and all the rest of the biotech things. But the whales remember, and they say you can’t be too careful.

Anyway, there she swam, I don’t know how she stood the cold, and then here came the orcas, and there was a lot of distant shouting and churning and blood and slapping the water and Daika kept swimming thataways instead of back to shore. Why in the name of earth’s long leg bones I could not tell you, then.

Then there were more shouts, lots of them, and the orcas skyhopping and the greys swimming north and the blood in the water spreading, spreading, and I saw it had been a calf and a big one, maybe the mother. “Daika!” I yelled, but she kept swimming. Earth’s teeth, should I go in after her? She was older than me, and a strong swimmer, while I only wimped around in the shallows maybe twice a summer. Yelling seemed to be the only thing to do, so I did it until my voice was hoarse. Also, I was running towards the cliff trail, and of course, that was the day that I stuck my foot into a hole and snapped my fibula just at the ankle, and, Earth’s ever loving leg bones, that hurt.

Which means I missed all the rest of what happened. I was rolling around feeling sorry for myself and making noises I hadn’t made since I was three. I didn’t see Daika and one of the youths from Eschrictius Clan come ashore. He must have looked an ugly fellow in that garish wetsuit, all swirled and speckled with yellow and orange designs. His face looked like a moon, I saw later, outlined in the tight-fitting red cap he wore, and speckled with moles. Daika always loved the moon, and she had apparently fallen in love with this guy several seasons back, just based on that moon face, I guess, and her romantic idea of what an Eschrictius man must be like.

The two of them sat on the beach for the longest time, kissing and carrying on. Talking, for all I know. It was Sally Darningneedle who found me. She was one of Mother’s interns, come to us from Seattle, looking to learn our wildcraft cooking. Cooks come in two sizes, it seems, one hard and round, and the other hard and thin. She was the hard and thin kind, not too happy to take time out to find out what was keeping Daika and me. “James,” she yelled as she trotted out into the meadow, the green and yellow silks of her gown matching the colors of the mustard plants and making her look like an animated plant. I wasn’t paying much attention to her words by then.

She picked up the full basket as though it were my fault that my bone was sticking out of my skin and said, “You stay here, I’ll get help. Where’s your sister?”

I didn’t answer, so the two of them had another hour or so on the beach together before I was taken care of and Sally went out again, looking for Daika. Her resemblance to an angry mustard plant was remarked on by Mother, so it wasn’t just me.

Luckily we had a healer staying the season with us, an incredibly tall woman, freckled with straying red hair tending to grey and, like many middle-aged women, with a Kali-kit, an extra set of arms temporarily bio-attached. She’d brought a whole muleload of equipment, with x-ray machine, angiogenesis enzymes, growth hormones, the works. It took almost a week before I could walk again, though. I don’t know why they can’t speed it up.

I spent the time propped up in John Pignose’s lab, learning more ballads and singing to the birds. John’s got a secret technique he wouldn’t tell me about, but I think it’s something to do with splicing altered neuropsin onto the genes that help them remember songs. Our meadowlarks are modified already, of course, and have been for a hundred years. We thought they needed a bit of help against the habitat changes they’d experienced since our human population expanded the way it did, and gave them a bit more memory and a bit more lifespan. What did they do with it? Not what you’d expect, no population expansion, no territory expansion. Well, actually, a bit of both, but that’s not what was important. What they did do, was go song happy. You couldn’t go anywhere without a meadowlark singing its head off at you.

John’s spent half his life working with the larks on that. The larks want to help, of course, we put that in a hundred years ago. They stood in line for the chance to get in on his ballad project, and he’s brought in dozens of bards over the years to feed them songs. Some of them can only learn one per breeding season, others can stuff five or six into their tiny little heads. Nobody knows if they understand them, but the males sure enjoy singing them, and their womenfolk? They remind me of human opera buffs.

So, I was singing when Alexsander and Daika came in, entwined with each other as though they’d invented lust and had to make sure not to forget any of the moves lest a single second of inattention made them forget. They made a dramatic couple, him so dark and her so fair. I’d spent so many years with Daika as my big sister, it made me stupidly jealous to see another guy put his hands on her. Wasn’t anything I wanted to do about it, though, nothing that I wouldn’t regret later.

Anyway, there they were. “Hey, James,” said Daika. “I’m just showing Alexsander around.”

“Good,” I said in a voice that meant “Bad.”

She ignored my snippiness. “We just came from the silkworm sheds. He’s never seen such big caterpillars before, have you Alexsander?”

“Nope,” said Alexsander, his thick pink lips forming the word in a shape that exactly matched the shape of his face. His voice was as deep a voice as I’ve ever heard. Maybe voice modification was something the northern clans liked to do, or maybe he was born with it.

“They only like the gene-mod salal we grow,” I said helpfully, just to show I didn’t hate his guts for touching my sister. Which I did, of course. Also, he had an edgy look to him that I didn’t like.

“I already told him about our operation,” said Daika. “How much silk comes from their cocoons, how they’re free to fly where ever but have to come back here to lay their eggs.”

Alexsander grinned, but it didn’t look like it came from the heart. It was a grin pasted on over some deep emotion. “Interesting, nothing like the cryotech stuff we do up in the Arctic.”

John Pignose wanted to hear all about that, but I certainly didn’t. Alexsander, with Daika hanging on him disgustingly, drifted off with John while I went back to the lark I was trying to teach. It’s not as easy as you would think. Last year, this fellow wanted that children’s song in 3/4 time about the greedy monster, but this year I couldn’t get him interested in anything in 3/4. I finally found one in 6/8, one of the jig-time harvest dances, and he was hopping around with excitement. I sang him the first verse about ten times before he had it letter perfect, though. John gets impatient with me if I take more than two repeats to get a song right, but that’s birds for you. Not an ounce more memory than they need in their heads, if that. Maybe I was a bit short with him because my setting fibula bone was itching like crazy.

I’d just finished with that lark and a new one was clamoring to begin, when Alexsander showed up, jittering his thumbs against his legs. “Where’s Daika?” I asked him.

“She’s gone back to help at the inn,” he said. “Said to stay here and watch you work.”

“Did she?” I was dubious.

He nodded. “I told her I sing, and she said I’d be interested in what you’re doing.”

I guess anyone would be. Pride of work took over, and I let the next lark in. He’d been fluttering impatiently at the window for some time. He was even less easy to please than the last one. No, nothing in 3/4. Nothing in 6/8. No 4/4 either. Well, that was just about all I knew to sing, back then.

“Mind if I try?” asked Alexsander. “I only do the one kind of song, though.”

“Suit yourself.”

He cleared his throat a few times. Sweat beaded on his nose and upper lip. He cleared his throat, gave a kind of whimper, and began. It was something Arctic and dark, his deep voice setting up resonances in my chest. A very odd sensation. One, two, three, boom, pause. One, two, three, boom, pause. “In spring nineteen two Mary Fisher,” and then he stomped his foot and paused, “Had a baby who wasn’t her husband’s,” stomp, pause, “Who loved him but sometimes he’d hit him,” stomp, pause, “And one day he broke the kid’s ribcage,” stomp, pause.

It went on and on for ten or more verses, a disjointed story that didn’t seem to have much of a point except to list misery and betrayal. I was not impressed.

The lark was. He pranced around excitedly, always a clear signal. Encouraged, Alexsander sang it to him again, and it took very few repeats before the bird had it down, several octaves higher, and flew off to impress the ladies with it.

John Pignose had wandered up to listen. “That’s quite a song you have there, Alexsander,” he said.

Alexsander looked miserable and nodded. “Yah. I’m burning my bridges,” he said with a very strange laugh.

“What do you mean?”

“Is that the time? I’ve got to run and help Daika,” he said, and rushed out the door, knocking over one of the perches as he did.

Over the next few days, Alexsander took over my job, to the point where I asked John Pignose if it was okay to teach the larks such brutal stuff. Adultery, abuse, and murderous pique, was that what we wanted our sweet birds to be learning? Alexsander wasn’t getting much pleasure out of the exercise, looked like.

“Well, James,” said John in his slow way, “we’ve got hundreds of birds out there singing thousands of ballads from around here. Now, they’ve got another kind of tune to spread to the world. I can’t help but think that diversity is good, whether in species or in song.”

“Yeah, but I don’t like them.”

“That lad has something on his mind,” said John. “But as for the songs? You’d do well to learn them yourself. You never know when that kind of rhythm and lyrics will come in handy.”

So I learned them, couldn’t help it really, not with my enhanced genetics and John’s training. There were over a hundred, one for each year since 1902, each one gloomier than the last.

“What’s the significance of 1902?” I finally asked Alexsander, the day before my leg healed and I could walk again.

“Well,” he said, and blushed. His skin was dark to start with, but even so, you could tell he was blushing because it got darker, and because a fine sweat suddenly sprang out on his forehead. “Well, it’s when we started.”

“No way,” I said, rudely. “I know my politics at least well enough to know that your Eschrictius clan was founded pretty much when whites came to the Northwest, back in the 1700’s sometime.”

“Well, yeah,” he said. “True. But it’s when my job was made.”

“And that would be?”

But he wouldn’t tell me, and got very uncomfortable. That night, he and Daika went on an even longer walk than usual. Talking, I thought to myself, and sniggered.

When neither of them showed up for work at the inn the next morning, Mother recruited me instead. “What do you think of Alexsander?” she asked me as we ground kelp into powder. As long as it was only for a few hours at a time, I loved helping Mother. The Mustard and Butterfly had an enormous earth oven, with stovetop, warmer, and twin bread ovens dividing the kitchen from the dining hall. It was always warm in there, and there was always something a growing boy could nibble on, and I loved the smell and the physicality of food. Plus, that was the last day of my healing and I’d gotten tired of John Pignose’s lab and having to watch the larks pick Alexsander’s tunes over mine.

“Don’t like him,” I said.

Mother actually laughed. “He’s a sweet boy,” she said. “But I think something’s weighing on his mind.”

“Daika’s weighing on his arm,” I said, sulkily.

“True enough. It happens,” said Mother. “Don’t stop work just because we’re talking, James.”

“Sorry.”

“You don’t know what it is?” she asked.

“Mom, he’s Daika’s age, not mine. He’s not going to tell me his secrets. And if he did, would I tell you?”

Mother laughed again. “I had to try,” she said. “He is dating my daughter. I don’t want her in over her head. At least I got him to take off that uncomfortable wetsuit and put on something more sensible.”

“Dating? What’s that supposed to mean?”

And then we had a long discussion of antiquated courtship terms, reminding me once again of how much things have changed since the dinosaur days of my parents.

As is often the way of such things, that afternoon Alexsander did tell me his secrets. I’d been sleeping on a bench in John Pignose’s lab and when I woke up, there was Alexsander, holding a mug of cold mint tea for me. “You got a minute?” he asked, and I nodded blearily, slurping at the tea.

“What happens to those birds?”

“What do you mean, what happens to those birds?”

“Well, what are you going to do to them?”

“We’re not going to do anything to them. What, you eat larks in the Arctic?”

Alexsander looked unhappy. “Fish and krill, mostly.”

“Krill?”

“Shrimp.”

“Oh.” There was a silence. I slurped a bit.

“So, what happens to the birds?”

“You keep asking that,” I said, impatiently. “Why don’t you just tell me what you are after.”

Alexsander looked even more unhappy. Then he got up and started pacing, his fists clenched. His moon face rode above his stocky body, like on a smoky night when there’s a fire set somewhere in the forest and the sky is raining ash. “You remember I told John I was burning my bridges?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, maybe I didn’t really mean it. Maybe I just was upset about what happened to Ooolooa and her calf. I tried to stop her, but that was a terrible thing to do, she’d rather die than let her baby die.” His face suddenly crumpled horribly and I was afraid he was going to cry, but he got ahold of himself. “And getting thrown off her back into the herring-filled waters off your island.”

“You don’t seem too upset about my sister, though.” I was a nasty teenager, I admit it.

Alexsander sat on the bench, keeping well clear of my almost healed ankle. “Your sister is fine, James. Don’t worry.” He put his head in his hands. “It’s me that isn’t fine, and Ooolooa that’s dead.”

I bit my tongue. Even I could tell that the value of smart-ass remarks was a bit skimpy.

“So, will you please tell me what you are going to do with those larks?”

“I told you. Nothing. They just fly away with a new song to sing.”

Alexsander did not take his head out of his hands. “Away? Where do they fly?”

“How should I know? I don’t ask them for an itinerary. They can’t write, anyway.” I began to giggle. “Why, you don’t like the idea of them singing your songs? You shouldn’t have butted in and sung them, that’s what.”

Alexsander got up and started pacing again. He was not a happy guy. “I shouldn’t have sung them.”

“Why not?”

“I’m the Secret Keeper.”

“So, they are secret?”

He groaned. “Not any more.”

Now I was more curious than irritated. “So, what kind of Secret Keeper tells the birds everything?”

“A very bad one,” said Alexsander. His voice cracked. “There’s nothing worse. I betrayed my people, for nothing more than grieving for my friend’s baby, for nothing more than being in a new land and thinking that nobody here could ever care about what goes on in my clan.”

“We learn about that early,” I said.

“Learn about what?”

“It’s for when we go on our Fluttering.”

Alexsander sighed. “And what would that be?”

“It’s after your initiation, you go off to flutter around for a year or two, or five, looking around, learning stuff that might be useful to the Butterfly Folk, maybe even finding a new place to live for a few decades or a lifetime. Most of us come back, but still.”

“Yes, so what is it you learn early, then?” asked Alexsander.

I shook my head. “I guess you guys must not have a Fluttering.”

“Whales don’t flutter.”

“Right. Anyway, they tell us that it’s easy to think that nothing you do in another tribe’s territory matters. That they’re not deep-down people, that all their strange customs means they don’t have customs at all. Nope, they tell us. Don’t go doing stuff that would make another one of the Butterfly Folk raise their eyebrows. Everyone that comes back says it’s a temptation.”

“I know,” said Alexsander. “It is.”

“So, they should have sent you through Orientation here. We tell our foreign interns the same and make sure they know it before we let them loose.”

“I’m not an intern. I don’t even know what one is.”

“I can tell. Same as a Fluttering, they all call it something different. Student, intern, apprentice.”

“I know apprentice.”

“Right. They come here to learn, and either stay or go on or go home. But we don’t let them crash around our lands without some kind of moral compass.”

Alexsander sat down again and put his head in his hands again. “So, I just betrayed my people, and you say that’s normal?”

“No, it isn’t normal. We usually listen to our teachers. Don’t you have teachers up there?”

Alexsander nodded. “The whales.”

“That’s it?” I tried to imagine what it would be like to be taught by a butterfly, and failed. Well, maybe we have learned from them. But still. Just whales?

“That’s it,” said Alexsander. His shoulders were tensed right up to his ears. “I can never go home.”

That was when John Pignose walked in. “What do you mean, you can never go home?”

Alexsander shook his head.

Well, I didn’t owe him anything. “He says he shouldn’t have taught those songs to the larks. They were a secret.”

John’s lined face looked grave. He’s an odd-looking man, and nobody can tell whether he got that way through gene-mod or was born ugly. I think that big nose helps him a lot when he’s working; he seems to work by smell as much as by sight or touch. Certainly, he doesn’t have any trouble with chemical analysis while the rest of us have to mess with dozens of reagents and enzymes and such. Anyway, his face looked grave. “How much of a secret?” he asked.

I thought back to the lyrics. Adultery, murder, and spite. “Pretty much,” I said. “If those songs were true, he’s just embarrassed dozens of people, maybe hundreds, big time.”

“Hundreds,” said Alexsander.

“So, they were true? Earth’s heart and liver!” John looked very upset. “Do you think your people will try to come down and kill our larks?”

I sat up. This was terrible. “War, you mean?”

Alexsander shook his head over and over. “I don’t know. I can’t go home, can I?”

“I doubt it,” I said, but he was looking at John.

“I doubt it,” said John. “Will anyone come to find you? What is a Secret Keeper? I’ve heard about them but what exactly do you do?”

“No,” said Alexsander. “Ooolooa and her calf died, I was riding her, and then I was gone. It happens. They’ll think I’m dead. And I might as well be.”

“So, what is a Secret Keeper?”

“Truth,” said Alexsander. “No tribe works well without somebody knowing the truth, they get unbalanced and can’t make good decisions.”

“True enough,” said John.

“But nobody wants their neighbors to know the bad stuff. So they tell the Secret Keeper.”

“And what does the Secret Keeper do with that knowledge?”

“Nothing,” said Alexsander. “We’re just supposed to know about it.”

We thought about that.

“So,” said John Pignose, “You’re new to the job?”

“Apprentice,” said Alexsander, miserably.

The next morning, my leg was finally healed, the adults had been talking all night with Alexsander, and he was sent off in tears with a mule and enough supplies to get him to the center of the continent before he had to stop and talk to anybody. The following morning, Daika was gone, and Mother was angry and snappish all day. She did send another mule after her, though, but Daika has yet to send word, and yet to pay me back for collecting those mustard flower heads for her.

Me, I spent the rest of season wandering around listening to larks in the field. Nobody ever swam ashore to see if our birds were singing their secrets out for everyone to hear, and really, nobody I couldn’t get the idea of Secret Keeper out of my mind, though. I started up my own list of secrets. I learned to swim. I watched the whales as they went by, imagining what it would be like to wear a red cap. To know everybody’s secrets and to keep the truth in sight.

The spring after my initiation year, some interns came and some went. Jennie the Bard joined us and I hope you don’t remember me just from her ballads. On a cloudy day in April, I pulled Alexsander’s wetsuit on and swam out to the whales as they went north.