|

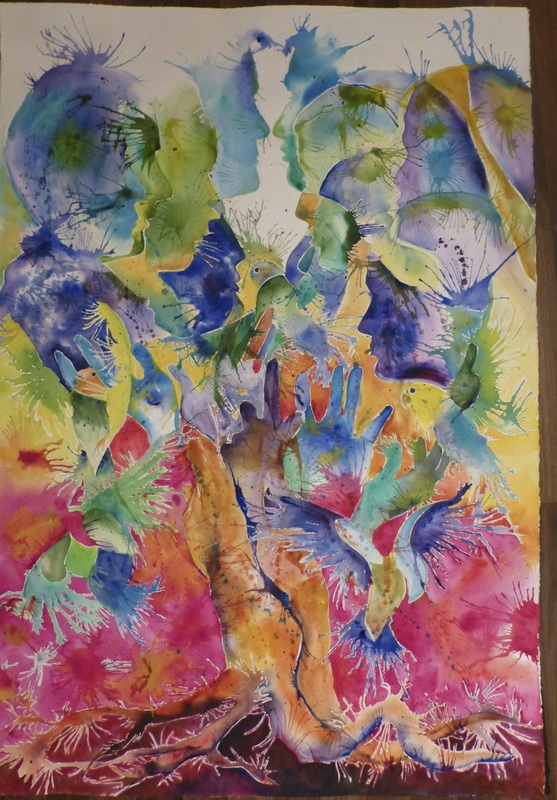

I went to Edinburgh in March to enjoy the company of my daughter and her boyfriend. I didn't bring my oil paints, but watercolors are portable, and the paper is relatively inexpensive. For this painting, I asked the two of them to stand so I could trace their shadows onto the paper. I like the idea of the movements of the subject and the different light sources and my own unsteady hand distorting the images so that there is a remove from the "real" image. Instead, all the filters we put up are part of the art. And then, of course, there are the vivid colors and the sheer fun of blowing the puddles of paint around all over the paper and a little bit onto their floor.

1 Comment

Sunday morning, of course one goes to church. But not just any church. Rosslyn Chapel, the setting for part of Dan Brown's "Da Vinci Code," is a 25 minute bus ride away.

It is a lovely little place. Outside, there is a notice that explains that it isn't so much a sermon in stone as an evocation of the very trees and birds. Perhaps. It was very nice, anyway. Some of the stone carvings were very new, and others were eroded beyond recognition. It was nice to see that they're actively repairing it. Inside, it was a perfect little church, peaceful and lovely. The congregation was small but of all ages. The service was the familiar Episcopalian one, and the sermon was on Mothering Day, today. I was struck again by the black/white tendency of Christian theology. The call to extirpate evil from all that we do, to follow only the good seems to me to be very dangerous. Not coincidentally, I just finished Carl Jung's The Undiscovered Self, in which, among other things, he says that when we repress something, when we don't admit that it is part of our human nature, then it finds some way of expressing itself anyway, but in a form that we don't recognize and hence cannot repress. Despite my queasiness about some of the things the minister said, I did enjoy his articulateness, and even wrote down one of his phrases, "The porridge-covered architecture (of northern Christian countries) and the strong East wind." On one of the walls near the altar was the phrase, "Forte est vina. Fortior est rex. Fortiores sunt mulieres. Supra omnes vincit veritias," which I surely will use for my Latin students. It comes from a Bible story where King Darius judges whether wine, the king, women, or the truth are the strongest. Guess which he picks? Afterwards, I talked with a woman whose husband had worked for the Scottish Salmon Board, but we never got that technical, which was too bad. We wandered about through fragrant wild onion, viewing the ruins of Rosslyn Castle and enjoying the river at its base. Jelte stuck his head in the water, which made everyone happy. We had greasy but tasty pub grub and then caught the bus back to town. Camilla and Jelte went off to look for John Napier's grave again, and again couldn't find it, while I napped. Then, the train to St Andrews through green and tidy countryside. Jelte says that he enjoys the crowding with the three of us in his micro-room. It's reminiscent of the African culture he grew up with. Indeed, as long as we have a place to go for much of the day, it truly is companionable. The dance of bodies, where we sidle past each other, take naps, and schedule showers, contributes human warmth to the meeting of minds that we also enjoy.

After a leisurely breakfast at the yellow cafe, the three of us walked (Camilla clattered in her wooden heels) through the stone lined streets towards the river, ducking precipitously down under the bridge to the packed dirt Dean Path that paralleled the ivy lined river. It rushes cheerily along, about 15 feet wide, enjoyed by strollers, dog walkers, and people with Important Destinations. Our Important Destination is the Modern Art Museum. Like the other museums I've visited, this one is small and elegant. The collection is not what I expected from its title. I suppose the word "Modern" also can mean "Contemporary." I'm pretty sure they intentionally arranged the displays on the left hand side of the building to move from purely representational art through the shattering events of the 20th century to complete dissociation. It was like watching the process of a schizophrenic breakdown. Bodies become distorted, then detached. Henry Moore's sculptures detach shoulders entirely from hips. Art dribbled off the canvas, became thicker, more textured, colors became less vivid or more fully saturated. Shared public visions, nuanced or broad, are replaced by cries of despair or private musing. More recently, it seems to me that fine art has become unmoored from any expectation. Anything from super-realism to full emotionalism to autistic motif repetition to cryptic layers of black shadow might appear. I find myself wishing that I could live another 200 years to see how this settles. In my opinion, the crumbling of the world order has not fully played out, as on the one hand, the developed nations must come to grips with loss of hegemony, and on the other hand, indigenous peoples must confront the presence of humans entirely outside of their mythologies. I believe, but of course can't prove that as things continue to readjust they will never fully settle. The world is blessed with a myriad of functional cultures, which are being forcibly united through technology, the Internet, English, and capitalism, but none of these factors needs to penetrate fully into the depths of culture. People might raise their babies differently once they have access to vaccines or education, but you will still be able to tell the difference between Swaziland parenting and Russian parenting. It may be that everyone will own a pair of blue jeans but they will also feel a connection to the saris, bunads, or kimonos of their ancestors. In the same way, art will never again homogenize the way it did, say, in the Celtic monastery tradition. There might be global advertising fads, but there will also be fine art that is fully rooted in culture, personality, and history. In the entryway, there was an anatomically precise twenty-foot resin sculpture of a newborn baby, still bloody from her recent ordeal, with one eye half open. The impact was intense. Babies hit us all, especially those whose hormones have been awakened through parenthood, in the instinctive part of our emotions. Another high impact exhibit was of four lifelike resin sculptures of men in rumpled business suits, one with a stick in his hand behind two men on their hands and knees, and once facing them with a mirror in his hand. It looked like a Situation, a setup where the menace was undefined but palpable. The final memorable piece, entitled War, was a shattered copy of Degas' touching sculpture of the 14 year old dancer (which I saw!! In Paris!!!). This one, though, was pregnant, with parts of her skin missing, some in an an anatomically believable way, others as though chunks of clay had fallen off. Wow. Afterwards the three of us sat in the sun on the terrace, drinking tea, getting foot massages, and enjoying each others' company. My goodness! 3:30! We galloped back home, stopping at a French cafe for some very good quiche. After naps and chill in' we headed off for an evening of clubbing. You heard me right. Clubbing. This is what the young and hip do in Edinburgh on a Saturday night. Also, this was St. Patrick's Day. The Old Town area, which is stony and staid by day, opens up at night. A couple days ago, I read an article in the Guardian saying that some shockingly high percentage of clobbers have accepted an unknown substance from a person they didn't trust and snorted it. I believe it. Buckets of alcohol flow, and remarkably convivial and mild mannered people crowd the streets and line up outside pubs. Everywhere is the smell of whiskey. Me, I'm taking meds which don't mix with booze so I was a bit out of my element. At the pub where we met with Jelte's business team, it was totally hopping! Bodies pressed against bodies, and everyone wore a smile. I tried to enter into the spirit of things but failed. The noise level was such that I couldn't make out individual words, just tonal barks. The only person I could understand was Jelte's stunningly lovely sister, whom I could lip read. I felt a bit like a curmudgeonly old codger who needs a hearing aide. At 11, when everyone moved to the dance club, I took my aging carcass off to home. The streets were magical, magical in the old sense of fey and unexpected and shadowed. Lights, colors, crowds and crowds of cheery youths, a marimba player, street people with their pit bulls settling down for the night, shouts and snatches of song, a quartet of women older and fatter than me in glittering green hats venturing out with maps clutched in hand. Not once during the 45 minute walk did I get a bad vibe. Under the impression that the Scottish Museum of Modern Art was near the National Gallery, I strolled through the gardens at the foot of the castle. Nope, the building that was marked with an A on my map search was the Scottish Academy, and a very friendly man explained this to me in seven different ways. He sent me around to ask directions at the National Gallery.

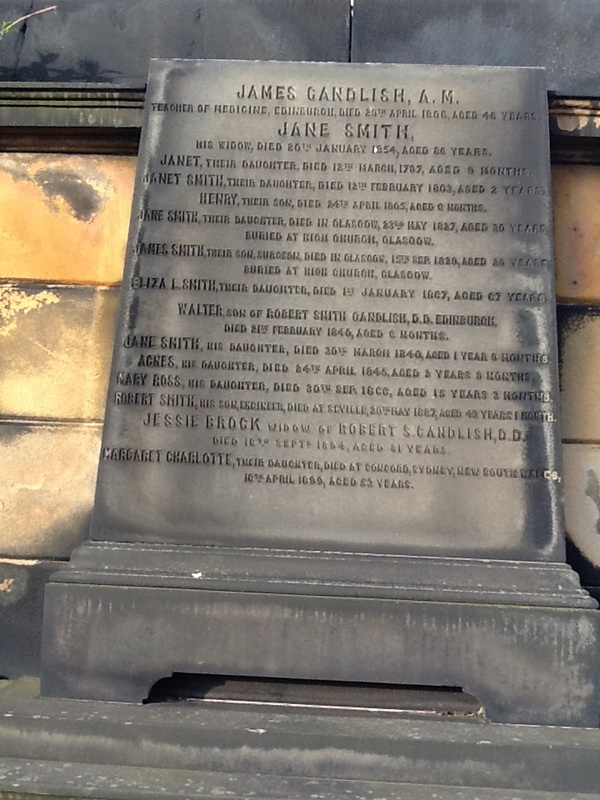

There was a burly bagpiper leaning against the fence, glowering at a younger version of himself who was piping in the courtyard. "Do you have bagpipe duels?" I asked, having been catapulted into a garrulous mood by the previous conversation and by my status of invulnerability as a tourist. He was having none of it. Glower was what he wanted, and glower was what he was going to do. "Duels?" he said icily. "No. We don't have duels." All right then. I was about to move off, but he relented and made an effort. You could almost hear the social engines in his brain start up. "Where are you from?" he asked. Then we got into a fascinatingly awkward conversation, where every time one of us spoke, the other one had just begun to speak as well. I would think that the conversation was over and move off, and he would call me back with a trivial question that was clearly designed to keep us engaged further. It could have been the subject of a thesis paper on conversational dynamics gone awry. But I did find out that the other piper and he traded off every half hour. So. Exactly the opposite happened at the National Gallery, where the guard at the door was the explaining kind of Scotsman. He waxed eloquent on the subjects of backpacks in the museum, and the impossibility of getting from there to the Museum of Modern Art. No direct buses, not possible to walk. This took a very long time to convey, so just for good luck I went through the museum again to steel myself for the long walk back to Jelte's flat. There I learned that Jelte was still not back from Aberdeen, having had a very successful yesterday talking with community energy mavens there, who pressed conviviality on him and made it seem ridiculous to travel back home without another shot first. This led to a home stay and friendship. I headed west to the Botanical Gardens, a map clutched firmly in hand. The map was of marginal help, since I didn't get the angles right. Streets are not orthogonal around here. You can head off and find that you have made a 30º miscalculation, which quickly veers off into walking in the wrong direction; erratic street signage doesn't help. It was quite amusing to be lost in a foreign metropolis. I found the Russian Embassy, next door to an unemployment office. I found an empty plinth where the statue of Flora Stevenson once stood. I bought pupusas at a food co-op, and met a crowd of people who looked like bikers at the entryway to a Baptist church that must have been a converted Catholic church. I walked along a stream and found a stone well with a statue of, possibly, Minerva. All in all, it was wonderful. I arrived at the Gardens in time to gallop around quickly, see amazing trees and flowers, and sit down in pouring rain to sketch the glass house and decide it would be better to head back than to waste time wishing my pen used waterproof ink. Which was a good decision, because just as I arrived at the flat, Camilla and Jelte arrived from opposite directions and we headed out for dinner. It was a genuine Italian restaurant with genuine Italian waiters. My plate of gnocci with artichokes must have been about a thousand calories a bite, but what bites! Rich, creamy, seasoned quietly but expertly. And finally, we headed off into the night at top speed, walking through parks, up hills, into stone passageways and through courtyards packed with wheelbarrows and plastic pipes and discovering a rock in a carefully racked gravel bed with a missing plaque and the carved inscription, "we find no vestige of a beginning and no prospect of an end" (from James Hutton, the guy who postulated that geological forces acted in the past just like we see them act today, and so we can deduce geological history), and passing by Athur's Seat and looking at maps in the window of a shop and viewing the place where squads of unhappy religious rebels had been hung (or maybe it was beheaded) and deciding not to look for Napier's grave because we had already gazed at Adam Smith's grave at another churchyard. Jelte and I spent the morning in a yellow painted café over coffee, croissants, and bacon. Then he left for a meeting in Aberdeen four hours away, and I went to the National Museum again, looking at machinery and animals this time. You get a sense of relentless sincerity. Device and schemes, plans and intricacies. The Scottish spirit includes buttonholing you and explaining it all carefully so you are sure to understand. It is a country of explainers. Afterwards I went to a Kurdish restaurant and spent a leisurely hour over shawarma and cardamom tea, while surreptitiously sketching my neighbors. The waiters were fascinated and kept coming over to see the progress. I got a very large date (from a palm, not for the evening) out of the deal. Replete, I climbed the castle hill, on volcanic dolerite. I wandered around in a high wind, but decided I wasn't ready to go in. Instead, I visited a tartan mill. The shop is one of those tourist destinations that is part museum, part jolly sales emporium. I made my way through china, pewter, and zillions of kilts to watch the weaving looms clatter away. I might end up painting some of these images some day... I love the concatenation of the built environment with the softer natural world. Despite the lack of raw nature in these images, there is something that speaks to me. Next stop, Calton Hill. At the top is an unfinished memorial to the soldiers who fought in the Napoleonic wars. Glasgow offered money to help finish the memorial, but rather than accept help from their rival city, the Edinburghers preferred it to remain unfinished. Perhaps the existence of an intense story like that gives the memorial some effectiveness? I sat and sketched the cityscape until realizing that my ears were tight and painful from the wind. Okay then. And there was the cemetery that David Hume is buried in! Wow! After some serious walking I ended up at the Greyfriar's Art Shop to get a calligraphy pen. There, a squinchy old man, a calligrapher for the courts of justice, advised me on ink (not India) and nibs (must have a reservoir, sold separately).

I whiled away the rest of the evening at the central library, reading calligraphy books and messing with designs in my sketchbook. I wandered up Lothian Road and then around to the Writers' Museum. You get to it by squeezing through a passageway between tourist shops selling kilts and cashmeres. In the basement was a plump volunteer with yellow hair and spectacles on a chain. She presides enthusiastically over the Robert Louis Stevenson rooms. You can see innumerable photos, pencil drawings, and touchingly trivial items from his life, like a fishing pole and an oyster shell he mailed to his aunt. In a glass case in the corner is a recent acquisition, a piece of art illustrating a scene from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, made from two books, ingeniously cut and glued and inked. Nobody knows who did it. Up narrow winding stone stairs are rooms dedicated to Robert Burns and Walter Scott. The curator, a very very black woman, said that she was struck by the heavy red paint and wood of the display rooms, the detailed etchings, and the wild primitive scenes that those authors loved to write about. Salad and sandwich at the Wiski Rooms. The drinking culture is well established here. I could have ordered whiskey for my lunch. Across what looks like a former moat to the National Gallery, with the usual fantastically amazing Rembrandts, Rubens', and Botticellis. I'm struck again by how clumsy the brushstrokes look up close. These dudes used very thin washes of paint, scribbled on any which way, layered densely. Afterwards, they sploshed varnish on with no regard for hiding the brush strokes. But oy, the art! Also, oy the Scottish art! In the basement (why the basement?) are some really amazing examples of Scottish art. There does not seem to be any particular school, but these lesser known works deserve more fanfare. I fell in love with Arthur Melville's "A Cabbage Garden." Then down and around to the Portrait Gallery, which had some good family portraits of Pakistani immigrants. My love of the absurd was tickled in the library, where there was a case of death masks made by phrenologists. You could see several murderers (who looked like ordinary guys, hmm), two female idiots, a Celtic Type, an English Type, and a Woman of Extreme Cunning. That made me inordinately happy. In the evening, Jelte and I went to Lord Maxwell McCloud's stone house next to the river Almond, a former mill I think. We entered a cosy round room, with signs of old glory such as a carved corner cupboard dated 1701 and truly extravagant tableware. There was Maxwell's minion Chris, and Norman Chalmers, a retired musician who used to be with Cauld Blast. Norman fascinated me. He had a rich but not incomprehensible accent, a heavy-lidded face with sagging but still fatty cheeks and lips, and an air of tightly clamped down wisdom. His attitude started out quite sour but despite himself, he became interested and talkative. He may be modeling himself on Robbie Burns, whom he has entirely memorized (says Jelte), and who liked to pass himself off as a simple peasant. I said that Isa was looking for a bagpipe, and Norman gave a scornful snort. "Ye can't find one for less than a tousand quid, and that's one that'll sound like shite," he said. When he realized that Isa was a woman, he snorted again and turned his chair so that he wouldn't have to face me. I said I would try looking in Greece and Maxwell suggested Bulgaria. Norman couldn't get over the horror of my wanting a bagpipe. It reminded me of the Japanese, who could never quite believe that Camilla and I could use chopsticks and liked fish and rice. Over several shots of whiskey and a fantastic, starch-heavy meal of kedgeree, rolls, and shortbread, Jelte told a story about when he was little. When he was five, his father explained to him that tomato ketchup is squeezed from the heart of a male lion. Two years later, when his parents moved from Swaziland to Holland, he was disoriented by all those white faces. When his teacher asked the rhetorical question, "Where does tomato ketchup come from?" his hand shot up. At last he had a chance to prove to his classmates that he wasn't just the "Bush Boy" that they called him. Ketchup, he said, is squeezed from the heart of a male lion. He hated that school. Maxwell countered with his own horrible school story. At home in the Highlands, there was an old Gaelic (pronounced Gallic) storyteller who would totter over to his cottage, and, leaning forward, shake his outsretched hands and tell stories.

Maxwell was two weeks into his boarding school when that same old gentleman appeared as a speaker in front of the assembled school. His subject was the Golden Eagle, and he had slides dating, Maxwell said, from the last century, glass ones. He had, at his age, no concept of interacting with his audience, he simple emitted his lecture to the hall of squirming boys. `At the end, when everyone breathed a sigh of relief that it was finally over with, he turned to the boys, shook his outstretched hands, and said, "Now, are there any questions?"' Maxwell wanted to make him feel good, and wracked his brain for some question to ask. "How many rabbits can an eagle eat in a day?" "What's that?" "How many rabbits can an eagle eat in a day?" "What's that? You'll have to speak up, laddie." "How many rabbits can an eagle eat in a day?" "Now then, this will never do. Come up to the stage and ask me properly." Red with embarrassment, Maxwell slunk up to the stage and repeated his question twice more. The answer? "How the hell should I know?" Then he leaned down from his great adult height and peered at the little first-year. "Great heavens! It's little Maxie!" And for two years afterwards, the older boys would greet him by peering down and saying, "Great heavens! It's little Maxie!" But there's more to the story. Seeing Maxwell's embarrassment, the Head Boy, Prince Charles, also stepped up to the stage to ask a contrived question. "He had then, and still does have, an enormous amount of graciousness and tact, does our Prince Charles." |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed